|

|

|

|

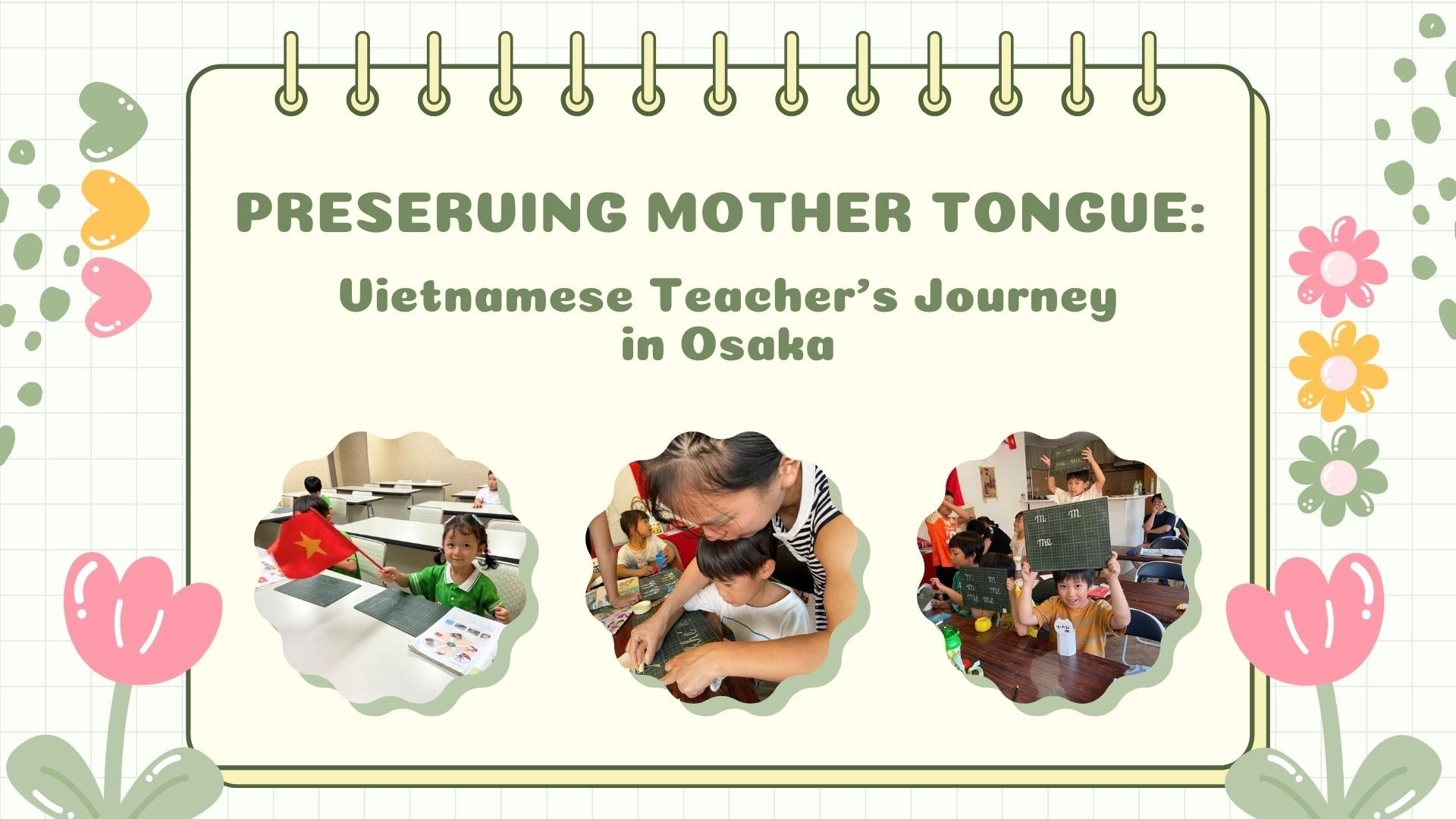

On weekend afternoons in Osaka, the Vietnamese class of Ngo Thi Dan once again echoes with children reciting traditional verses. The lines of “Ve vẻ vè ve…” rise slowly from their voices, sometimes slightly mispronounced, yet always full of effort. For Dan, that familiar sound has become an indispensable part of her life over the years. Teacher Dan moved to Japan with her husband for his work in 2018. During the first years away from home, she spent most of her time taking care of her family and adapting to the new environment. By 2023, when her second daughter had grown older, she decided to volunteer as a teacher at the Cay Tre (Bamboo) Vietnamese Language School, marking the beginning of her journey accompanying children of Vietnamese origin in the Kansai region. |

|

Ngo Thi Dan volunteers as a teacher at the Cay Tre Vietnamese Language School. |

|

During her teaching experience, Dan particularly remembers a little girl who had gone through a period of almost completely losing her ability to use her mother tongue despite being born into a fully Vietnamese family. When she was younger, the child could still say a few Vietnamese words, but as she grew older, studying and living entirely in a Japanese-speaking environment caused her Vietnamese to gradually fade. By the age of 5 or 6, she could barely communicate in Vietnamese and would even feel confused and avoidant whenever her parents encouraged her to speak it. This “overlapping” of languages led to signs of confusion, affecting her learning at school. The moment the child told her mother that she “could not speak Vietnamese anymore” was also the moment her parents were forced to halt Vietnamese lessons at home - a decision that, according to Dan, is very difficult but not uncommon among Vietnamese families trying to adapt to a fully Japanese environment. It was only after learning about the Cay Tre Vietnamese Language School that the child’s mother brought her in for a trial lesson. During her first class, the girl hardly spoke on her own; she only repeated simple words when instructed, and many explanations had to be relayed through her mother in Japanese. Understanding the child’s psychological sensitivity and her receptive capacity, Dan chose to progress slowly: rebuilding her basic phonetic and vocabulary foundation, creating a gentle communication environment, and allowing the child to gradually grow familiar with hearing and speaking Vietnamese without pressure. |

|

Ngo Thi Dan patiently guides a student in class. |

|

According to Dan, the most important factor is not speed, but perseverance - the perseverance of the teacher, the child, and the parents. The family lives about 20 km from the school, yet the child asks her mother to take her there every week. The weekend classes gradually became a foundation that helped her regain Vietnamese naturally. In an environment with peers her age, she became more open, began using simple Vietnamese phrases again, then started reading, and eventually developed a passion for practicing her writing. Today, after three years of studying, she can converse with her grandparents and relatives in Vietnam more naturally, without her parents having to “interpret” as before. What Dan remembers most, however, is not the child’s level of improvement but the simple motivation she once shared: “I love Vietnam, I love Vietnamese, I want to talk to my grandparents.” For Dan, this is not only the result of a learning process but also clear evidence of the vitality of the Vietnamese language when children are placed in an appropriate environment with the support of their families and community. |

|

| Teaching Vietnamese to children of Vietnamese origin in Japan, according to Ngo Thi Dan, is a journey full of challenges. The greatest difficulty comes from the wide disparity in students’ language proficiency: some children speak Vietnamese quite well because their families maintain daily communication; some only recognize a few words; and there are cases where children can hardly speak Vietnamese at all. The class also includes students aged 5 to 13, resulting in very different learning paces and linguistic approaches among the groups. |

|

Ngo Thi Dan’s classroom creates a cultural foundation that helps children feel naturally closer and more connected to Vietnam. |

| The second challenge lies in teaching materials. There is currently no dedicated Vietnamese-Japanese bilingual curriculum for children of Vietnamese origin, so she mainly uses Vietnamese textbooks from home and adapts them herself. She often simplifies concepts, introduces visual cues, or connects lessons with Japanese culture and geography to make them more relatable. For instance, to explain the term “ancient capital,” she immediately refers to Kyoto - a place with a similar historical role to Hue in Vietnam. For her, teaching Vietnamese abroad is not simply “teaching letters,” but building a cultural foundation that helps children feel closer to and more naturally connected with the language. |

|

The children in her class rehearse performances and join games during the Mid-Autumn Festival. |

| Alongside this, Dan builds a teaching method based on experience. Each lesson incorporates music, folk rhymes, and traditional games such as “cat and mouse,” “o an quan,” and hopscotch. These activities help children absorb Vietnamese more gently, reduce pressure, and spark their interest. “Children love singing and playing, so I put all of it into the lessons. When they are happy, Vietnamese comes to them naturally,” she said. |

|

The children watch a water puppet performance. |

|

Her challenges were partly eased after she participated in the 2025 Training Course on Teaching Vietnamese for Teachers of Vietnamese Abroad organized by the State Committee for Overseas Vietnamese Affairs (from August 13-28, 2025). There, she was introduced to new pedagogical methods specifically designed for Vietnamese children overseas - students who learn Vietnamese as a second language. One important change she applied after the training is shifting from teaching letters and phonics sequentially to teaching by sound-rhyme groups and communication themes. This method not only supports letter recognition but also helps children use Vietnamese in specific contexts. As a result, they can form short sentences, remember vocabulary, and apply what they learn in familiar daily situations. The thematic approach also helps address proficiency gaps. In a lesson on family, school, or familiar objects, more advanced students can expand their vocabulary, while beginners can still participate and grasp the essential content. |

|

Teachers participated in the 2025 Training Course on Teaching Vietnamese for Teachers of Vietnamese Abroad organized by the State Committee for Overseas Vietnamese Affairs (August 13-28, 2025). |

|

The training course also equipped her with visual tools, worksheets, and illustrative materials that overseas teachers can adapt to their classroom conditions. These changes have made Vietnamese lessons more relaxed, practical, and interactive. Many parents shared that their children have begun asking, “What is the Vietnamese word for this?” or using more Vietnamese in daily life. For Dan, participating in the training not only helped her improve her teaching skills but also strengthened her belief that her efforts are not solitary. She now has a network of teachers from various countries - a place to exchange experience, seek materials, and, most importantly, a foundation to develop Vietnamese teaching in a more systematic and sustainable way. “As long as the children can say one more Vietnamese sentence or understand one more word about their homeland, I feel that every effort is worthwhile,” she said. For her, the journey to preserve Vietnamese abroad is not merely volunteer work, it is a connection to her roots, ensuring that each child growing up in Japan keeps a part of the voice of their homeland. |

|

By Mai Anh Published on: December 09, 2025 |