|

In the evening, the room of Trang’s family is always filled with laughter. The two children - Gia Bao (11) and Quynh Anh (7) - sit beside their mother on a small bed. “Now it’s your turn - name Vietnamese dishes; whoever makes a mistake loses,” Trang announces the rule. Gia Bao quickly says, “Beef pho!” Quynh Anh giggles, “Chung cake!” “Mom adds: Hue beef noodles,” Trang smiles, tilting her head slightly, waiting for her children to continue.

The Vietnamese word chain game has become their nightly routine. In the original version, each player says a word that starts with the last sound of the previous one. But since her children’s Vietnamese vocabulary is still limited, Trang chooses simpler themes - naming foods, animals, or familiar objects, so they can play and learn at the same time. “We compete, and whoever wins gets a small reward,” she says. “Slow and steady. Just a little each day, but regularly, and the children will remember and love Vietnamese as they love their own blood.”

|

|

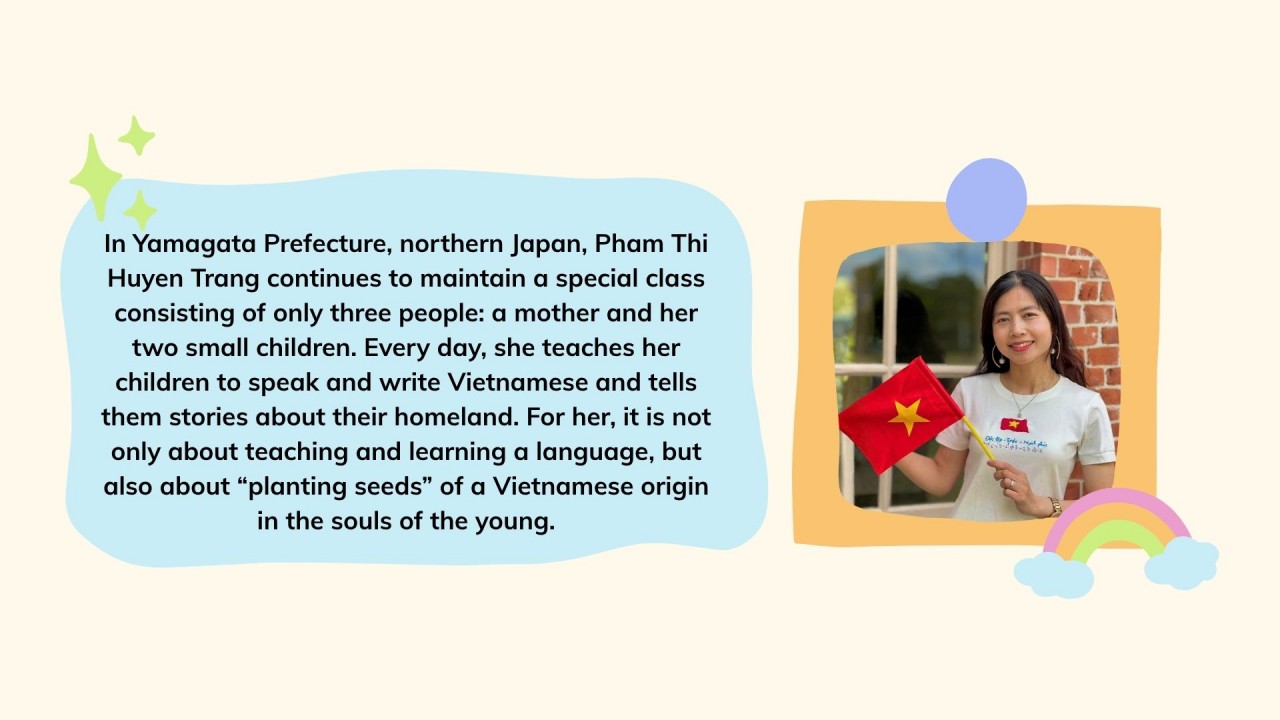

| Pham Thi Huyen Trang's family in Japan. |

Born in 1987 in Ninh Binh Province, Trang graduated from the Faculty of Literature (University of Education - University of Da Nang) and from Hanoi Law University. Her journey to Japan began with her work at the Vietnam-Japan Kindergarten in Da Nang, where she met her future husband, Koga Kenji, an employee of the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO).

“Among many JETRO staff, he was the only one who chose Da Nang to study Vietnamese. He often came to the school to help out and asked me to correct his pronunciation. From those lessons, we gradually became friends, then fell in love,” Trang shares.

A year later, Kenji returned to Tokyo for work but continued traveling to Vietnam frequently. “He later confessed that he volunteered for every business trip to Vietnam just to see me,” she laughs. They married in 2012. Since then, their family has lived in Hanoi, Osaka, and Yokohama, and now settles in Yamagata. Life is peaceful, but Trang always worries that her children might forget their mother tongue. “I’m afraid one day they’ll go back to Vietnam and not be able to talk with their grandparents, so I have to start early to help them understand and stay connected to their roots.”

|

At home, Trang speaks Vietnamese with her children, while her husband uses Japanese. Even though Kenji understands and speaks Vietnamese, she insists on keeping this rule. “Japanese pronunciation of Vietnamese sounds very different, so I’m afraid the children might be influenced. I keep speaking Vietnamese; they understand but usually reply in Japanese. I just keep repeating until they answer in Vietnamese.”

|

| Trang’s children learn to make Banh Chung. |

Before starting primary school, Trang began teaching them the Vietnamese alphabet, spelling, and reading comic books in Vietnamese. During holidays, she decorates the house, lets the children cut out the words “Tet” and “Spring,” hang parallel sentences, make floating rice cakes, wrap chung cakes, wear ao dai, and listen to Tet music together. “They ask: ‘Mom, what word are you making? What is this? What does it mean?’ I answer while teaching them letters and meanings,” she says.

|

| The children decorate the living room for Tet. |

Without a formal classroom, she turns daily routines into language lessons. While cooking, she teaches them to recognize ingredients: “This is onion, this is garlic, this is potato…” When they go to the park, she points things out: “This is a slide, this is sand, this is a small stream…” The whole family records videos, practicing speaking and describing things in Vietnamese. “I think teaching Vietnamese should start from familiar things - the closer they are, the longer the children remember,” she says.

|

Teaching Vietnamese in Japan, according to Trang, is difficult because there’s little environment for practice. “I try to speak Vietnamese 100% at home, but the time at home is short. The children go to school, join extracurricular activities, and play with Japanese friends. In the evening, they do homework and prepare for the next day-there’s hardly any time left to talk in Vietnamese,” she explains.

|

| Trang's children attended Vietnamese Festival in Japan |

In her neighborhood, there are few Vietnamese families. The children only meet other Vietnamese kids on weekends, but when they do, they often switch to Japanese for convenience. “They’ve lived in Japan since birth; their Japanese is excellent, but their Vietnamese is weak. Even when they meet to practice speaking Vietnamese, if parents don’t remind them, they switch to Japanese quickly so they can understand each other and play faster. When I ask in Vietnamese, they reply in Japanese-just to answer faster and go back to playing or watching TV. When Japanese friends are around, they’re even more reluctant to speak Vietnamese, afraid their friends won’t understand,” Trang says.

Her two children are currently following the Vietnamese curriculum, her son is in the second semester of third grade, and her daughter is in the second semester of first grade, but their communication skills still lag behind. “They can read and write fairly well, but their speaking is short and grammatically mixed because they don’t have enough practice,” she shares.

|

| The children decorate the house for National Day. |

Trang hasn’t enrolled them in in-person Vietnamese classes because the centers are far away and their schedules conflict. “I let them take online Vietnamese classes with a few other kids, so they have a chance to practice and communicate,” she says.

|

|

| Non La “made in Vietnam” at the Hanagasa Festival in Yamagata, Japan. (Photo: NHK) |

The Hanagasa Festival - one of the largest in the Tohoku region - requires thousands of floral hats for the dancers each year. But since 2024, the number of Japanese artisans making these hats has dropped sharply, causing a shortage of more than 1,000 pieces.

|

| Artisans from Giai Tay village, former Ha Nam Province, making Hanagasa hats. (Photo: NHK) |

The director of Shoubido Company, the main hat supplier, reached out to Trang’s husband, Koga Kenji, JETRO’s Chief Representative in Yamagata, for help finding overseas production partners. Seeing the Hanagasa hat, Kenji immediately thought of Vietnam’s conical hats. “During Tet, our family often wears conical hats and ao dai. That image made my husband think Vietnam could make them,” Trang recalls.

Kenji brought one of their Vietnamese conical hats to show the company. When placed side by side, the Japanese partners were amazed. The Vietnamese Non La was lighter, more graceful, and had a naturally soft curve. From that moment, the idea of collaboration with Vietnam was born.

After visiting former Quang Binh and Ha Nam provinces, the team chose a workshop in Giai Tay village (Ha Nam), a place with a long tradition of hat weaving. “At first, the artisans were unsure because Japanese hats have flat tops and use distinctive green nylon thread. But after one night, with their skill and creativity, they produced perfect Hanagasa-style samples,” Trang recounts.

Representatives from Shoubido were pleasantly surprised. The “made in Vietnam” hats met all standards - lighter, easier to dance with, and reasonably priced. However, mass production was not easy. The special green thread used for the decorative patterns was hard to find in Vietnam, and the Lunar New Year holiday further delayed progress. “The artisans had to search everywhere for materials and worked almost nonstop to meet the deadline,” Trang says.

|

| Pham Thi Huyen Trang with a Non La at the Hanagasa Festival. (Photo: NHK) |

In the end, 1,500 hats were completed and delivered to Japan on time. During the 2025 Hanagasa Festival, more than 10,000 participants danced under the summer sun, their Vietnamese-made hats shining white, spinning gracefully to the rhythm of the drums. Trang’s family was there that day, proud to see a touch of Vietnam contributing to Japan’s cultural celebration.

“When the news came on TV, my kids shouted, ‘Papa! Mama!’ and said, ‘I love conical hats, I love Vietnam!’ That alone made me so emotional,” Trang recalls. “My greatest pride is not just bringing Vietnamese conical hats to Japan, but also helping spread the beauty of Vietnamese culture to the world.”

After the Hanagasa Festival, Trang’s small house returned to its peaceful rhythm. In the evening, the three of them still play word games, read, and tell stories in Vietnamese.

“Like many Vietnamese parents abroad, I only wish for my children to speak Vietnamese and understand their homeland’s culture,” Trang says. “One day, when our family gathers and the children can talk with their grandparents in Vietnamese, that will be the happiest moment of all.”

For her, preserving the Vietnamese language is also preserving Vietnamese culture. “Every Vietnamese living abroad is trying to keep our language and culture alive. The most wonderful thing is when the next generation continues that tradition,” she shares.

Beyond teaching her own children, Trang also works to promote the image of Vietnam through cultural exchange activities. After successfully connecting the production of floral hats for the 2025 Hanagasa Festival, she and her friends are continuing new orders. “We hope to keep this activity going every year, as a way for Japanese people to learn more about the beauty of Vietnamese people and culture,” she said.

| By Thanh Luan Design: Mai Anh Photos & Video: Courtesy of the Interviewee |